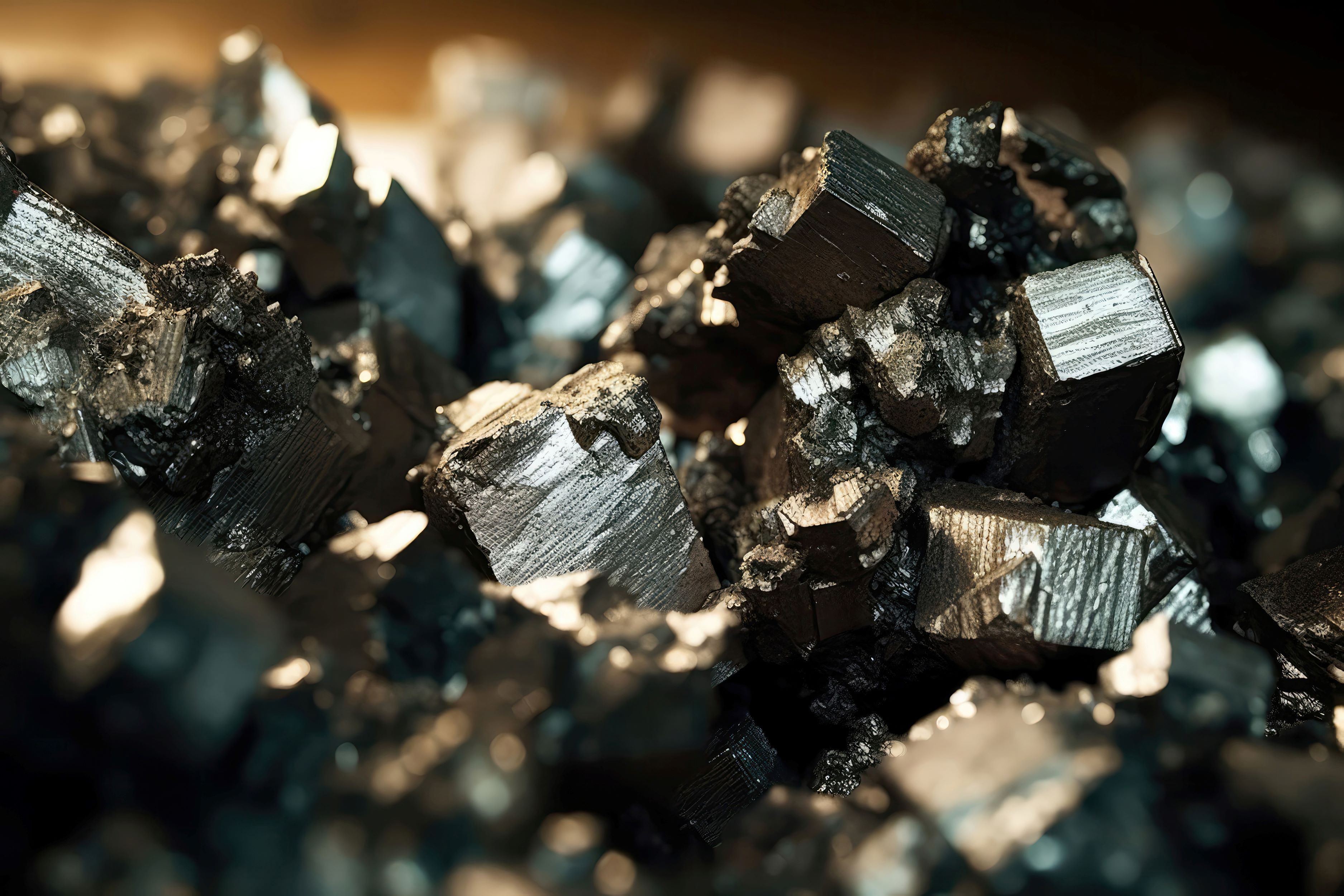

The Daily Update’s series on global commodities turns its attention this week to another critical mineral: nickel.

As with lithium and cobalt, nickel is a critical mineral seen as vital for the green transition.

Until recently, the major use of nickel was its use in the production of stainless steel to provide resistance to corrosion. According to the Nickel Institute, the metal can be fully recycled and is highly resistant to corrosion and oxidation.

However, in recent years it has been increasingly used in the production of batteries for electric vehicles (EV) and other modern technologies such as smartphones and laptops.

According to Roger Marshall, trade and customs specialist at the Institute of Export & International Trade (IOE&IT) and an expert in critical minerals, its use in the green transition has led to a forecasted shortfall in nickel, as the average amount of nickel used in an EV is 15-30kgs, which requires a significant amount of mining.

Growing demand

As a result, the International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that demand for nickel will grow by at least 65% by 2030.

As it stands, 50% of the world’s supply of nickel comes from Indonesia. Russia and the Philippines are the two next largest suppliers but rank significantly behind the leading nation. Historically, Canada was a major supplier but has dropped off in recent years.

In 2020, the Indonesian government banned the export of nickel ore, as it wanted to ensure the nation benefitted from the development of operations producing nickel metals, as well as from electric battery plants. Marshall says:

“This initially caused a spike in the world price but now prices have fallen by 40%, reflecting a more balanced market.”

Environment

A major issue for nickel – as with other critical minerals – is the environmental impact of mining.

Marshall explains the reasons behind the high environmental cost of nickel mining:

“As with many of these minerals, the processing is environmentally challenging.

“The two processes are either hydrometallurgical (by flushing and filtering for separation) or pyrometallurgical (through heat and melting). Although there have been improvements recently, these are very energy intensive and produce a lot of negative side effects."

For Indonesia in particular, the nature of the deposits can make the process even more damaging to the environment.

“Indonesia’s reserves are made up of Nickel Laterite, which is a much lower grade of nickel, and it is very carbon intensive to extract the nickel ore.”

All of this creates a cost, one often paid by vulnerable and indigenous communities.

In July, the BBC reported that deforestation and pollution were destroying the traditional way of life for members of the Bajau people, an indigenous community that hunted for fish and lobsters via freediving.

Villagers elsewhere in Indonesia have been reporting similar environmental problems, according to Euronews.

Trade issues

In spite of the environmental cost, Indonesia sees nickel mining as a vital part of its economic future.

Its spot as a global supplier faces challenges, however, as geopolitical tensions between China and the US spill over.

China has invested heavily in the Indonesian industry, as China relies heavily on imported nickel in its own domestic manufacturing.

As a result, the US Inflation Reduction Act is creating problems for the Indonesian industry, says Marshall:

“Indonesia appears to be excluded from taking advantage of the subsidies created by the act. At the moment, Indonesian material does not qualify for any support because of the large involvement of Chinese finance in its production. It also does not have any free trade agreements with the US.

“The Indonesian government is aware of this, and metal companies are looking at ways to enable the product to qualify for US subsidies, but this is a potential issue which could see the nickel industry move to other players such as Australia or Brazil.

"However, both these countries have issues on the environmental side for ramping up nickel production.”

Brazil and Australia have major reserves of the critical metal. Private backers, such as Glencore and Stellantis, are part of a US$1bn deal to fund the Santa Rita nickel sulphide mine alongside the Serrote copper mine, both in Brazil.

South Korea has also invested in building its capacity, with Korea Zinc currently constructing a plant that would make it one of the largest producers of nickel sulphate.

Fraud

Global nickel supply chains have been shaken in recent months by a series of fraud allegations lodged by a number of trading houses.

Trafigura, one of the largest global commodity suppliers, has launched a legal case over US$590m of alleged nickel fraud against multiple defendants after it claimed that metal cargoes it purchased did not, in fact, contain the nickel they were supposed to.

The company said that, in late 2022, it conducted an inspection of warehouses in Rotterdam and found that the shipments contained no nickel.

Other companies, like Kataman Metals, have launched similar lawsuits recently, and the industry has faced questions over forged receipts and empty warehouses in recent years.

The future

As with other sought-after metals whose suppliers are facing supply chain and geopolitical issues, governments and private companies are exploring alternatives.

“As with all minerals there is work to look for alternative solutions for battery design without or less nickel,” says Marshall, pointing to other sources, like lithium manganese oxide batteries, that have been used as an alternative.

While the performance of nickel batteries still significantly outperforms other batteries, technological advancements could result in the adoption of a nickel-free alternative.